It’s a 25,000-piece puzzle that researchers have longed to solve. That’s because the 25,000 fragments represent the Dead Sea Scrolls, and inside are ancient secrets — mysteries that have been locked away for 2,000 years.

For more than two decades, Brent Seales has doggedly labored to help solve the puzzle.

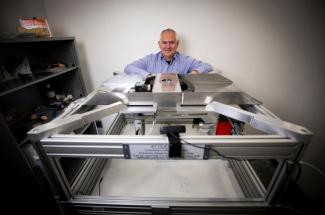

Seales, professor and chair of the Department of Computer Science at the University of Kentucky, is considered the foremost expert in the digital restoration of damaged and unreadable manuscripts. To this day, his quest to uncover the wisdom of the ancients is ever evolving.

Now, Seales and his dedicated team of staff and student researchers are one step closer.

“We are using technology to reveal new text from some the world's most storied collections. While the invisible library of texts obscured by damage represents an immense technical challenge, it holds massive potential for discovery,” he explained. “The significant progress we are making with fragments from the Dead Sea Scroll collection inspires us to keep working toward a comprehensive set of tools for revealing every manuscript in the invisible library.”

Dead Sea Scroll Discovery Made Public

In November 2018, the Israel Antiquities Authority (IAA) invited the team, commonly referred to as the Digital Restoration Initiative (DRI), to continue their work on the Dead Sea Scrolls. Micro-CT scans were conducted on five items from the collection, including a small fragment found in Cave 11 at Qumran in Israel's West Bank.

The following spring, Anthony Tamasi, a computer science undergraduate in the College of Engineering, began working on the data. Using cutting-edge technology, he was able to virtually unwrap five layers of the multi-layered fragment to reveal clear images of ancient writing.

“When I first saw the text inside the scroll, it felt like I was a kid again — like digging through the sand for fossils at one of those museum exhibits and actually finding one. I was so excited,” Tamasi said. “I was the first person to see the contents of the scroll this millennium. There aren’t many opportunities like that.”

Breakthrough Unlocks New Challenge

"Some 30 characters have been recovered from the various unwrapped layers. The beautiful letters can be easily deciphered, but the extant text is still not enough to recognize whether it is written in Hebrew or Aramaic,” Oren Ableman and Beatriz Riestra, the scholars from the IAA charged with deciphering the text, said. “The continued research of the digital restoration and the possible detection of any further traces of ink recovered using the imaging analysis of the DRI will make it possible to read a text that is still a mystery.”

Scholars from the Jewish Studies Program in the UK College of Arts and Sciences were also excited by the results of the imaging technology and the newly discovered letters.

“The script itself is Aramaic 'square' style (Ashurit script), which is the same writing system as what one would recognize as written Hebrew today,” Jim Ridolfo, an associate professor in Jewish studies and the Department of Writing, Rhetoric, and Digital Studies, said. “But at the time the Dead Sea Scrolls were penned, Ashurit script could be used to write Aramaic (the language) or Biblical Hebrew. Qumran also contained paleo-Hebrew manuscripts such as 11QpaleoLev, as well as Aramaic texts written in Ashurit, so both scripts and languages were present at the site.”

For now, what can be said is that Seales’ team has revealed a set of clearly defined characters in the square Hebrew script, which is very similar to the modern Hebrew square script, that is typical of Hebrew and Aramaic manuscripts of the time. Because Hebrew and Aramaic use the same script, individual characters are not sufficient evidence on their own to draw conclusions about the language used to pen the text.

“For an example, if we revealed the letters NEC, I couldn’t conclude that the language of the document was English or Spanish, because I could very easily be looking at 'NECESSARY' or 'NECESARIO,'” Eric Welch, a senior lecturer in the Lewis Honors College, added. “In the same way, a small set of characters makes it difficult to determine which biblical text this might be. What Brent’s team has done is marvelous, and it’s only a matter of time before we can start to answer these questions.”

Such questions inspire Seales’ team. “Working on the Dead Sea Scrolls project has encouraged me to be more open to computer science opportunities in different fields, like the digital humanities,” Tamasi continued. “The experience helped me realize that computer scientists and software engineers can make a direct digital impact on just about anything, including things like scrolls that have been thought of as explicitly physical.”

Seales and Team Make Unprecedented Breakthrough in 2015, Reveal Biblical Text

In 2015, Seales used the revolutionary technology to read parts of an ancient Hebrew scroll — part of the IAA's state collection of scrolls — for the first time.

In 1970, archaeologists unearthed the scroll in En-Gedi — the site of an ancient Jewish community near the Dead Sea that flourished during the Byzantine period. According to researchers, a fire destroyed the site in 600 CE (A.D.), leaving behind charred scrolls of parchment.

The animal-skin document was badly burned. So delicate, just touching its surface sent pieces flaking off. Attempting to read it by physically unwrapping the layers would destroy the artifact beyond repair.

The scorched En-Gedi fragments remained in storage for more than 40 years. Meanwhile, archaeologists believed the contents — if they could ever be read — would be significant.

That turned out to be the case, when Seales was asked by the IAA to attempt his newly developed "virtual unwrapping" method. In doing so, he discovered the beginning of the Book of Leviticus. Believed to have been written between the second and third centuries CE (A.D.), the text represents the oldest copy of a book of the Bible discovered in Israel after the Dead Sea Scrolls.

The discovery solidified Seales’ reputation as “the man who can read the unreadable.”

"The text revealed from the En-Gedi scroll was possible only because of the collaboration of many different people and technologies," Seales said. "The last step of virtual unwrapping — done through the hard work of a team of talented students — is especially satisfying because it produced readable, identifiable, biblical text from a scroll thought to be beyond rescue."

The Technology Behind the Discoveries

Seales’ unprecedented work to restore damaged manuscripts culminated with the development of the Volume Cartographer — a revolutionary computer program for locating and mapping 2D surfaces within a 3D object. The software pipeline, which is the engine that drives virtual unwrapping, is used on extremely high-resolution micro-CT images — enabling scholars to read a document without ever needing to physically open it.

The first stage, “segmentation,” isolates the surfaces of the document from within the scan and produces a 3D model for each page. Next, the “texturing” stage searches the dataset for ink signal and embeds that signal onto the surface model. The final stage of the pipeline, “flattening,” transforms the 3D surface into 2D images that scholars can easily read.

Moving Forward

While the first-of-its kind software has profoundly impacted history and literature, not all damaged artifacts are created equal.

The team is continuously developing new algorithms designed to better address challenges. Their latest approach utilizes convolutional neural networks and machine learning techniques to automate the segmentation process and to identify signals for carbon ink, which is notoriously difficult to detect using micro-CT.

And though, at times, progress is slow, and breakthroughs seem distant, Seales remains optimistic. He's confident that it's only a matter of time before artifacts deemed “unreadable” succumb to modern technology and, more importantly, to his team’s determination.

“Our next step is to grow the Digital Restoration Initiative into a world-class imaging and restoration lab,” Seales said. "Overcoming damage incurred during a 2,000-year span is no small challenge. But facing big challenges with grit and innovation, and inventing a new way forward, is exactly why students like Anthony Tamasi come to the University of Kentucky."

You can view a 3D rendering of the Dead Sea Scroll fragment here.

The scans of the fragments were made possible thanks, in large part, to a generous gift from Lee and Stacie Marksbury. Both UK alumni, Lee graduated with bachelor's degrees in economics and history, while Stacie earned a bachelor's degree in elementary education.

"After seeing Seales’ and his team's work, Stacie and I were absolutely blown away. The technology and technique were fascinating and something we never imagined possible," Lee said. "Beyond that, however, was the information that could be successfully unlocked. The idea of these documents being read for the first time since antiquity was something we did not hesitate to get behind."

To complete the Dead Sea Scrolls project, funding remains imperative. More information about the Digital Restoration Initiative, and how you can get involved, can be found online.

This article originally appeared on UK NOW - University of Kentucky News on July 23, 2020. You can view the article here.